Jamaica

Précis on the Cultural Map of the Multilingual Formation in Zong! – Wenjia Yang

This collection of pictures is about the imaginary moments of the origin of Jamaican Creole represented in Zong!. Impressed by the variety of non-English languages in the book, I traced the foreign words listed in Glossary, located the words I can identify and numbered them in a code which combines page number and line number of each word. For example, I marked the first word in Glossary, the Arabic word rotl, as 13824, which means the word is located on page 138 line 24, while English words are not marked. By setting a horizontal axis as the code and vertical axis as the amount of words on the same spot, I intended to visualize the linear process of reading as a temporal activity and highlighted the encounters with non-English words. With the technical help from my friend Sili, we created four pictures reflecting the relationship between diverse languages in Zong! with the statistical programming language R, another kind of language.

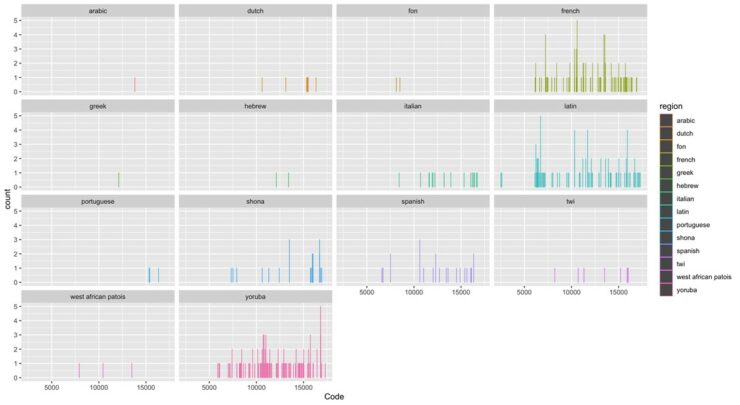

The set of bar charts includes 14 kinds of languages listed in Glossary, respectively as Arabic, Dutch, Fon, French, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Latin, Portuguese, Spanish, Shona, Twi, West African Patois and Yoruba. The respective bar graph reflects the amount of words of the languages appeared in sequence of pages and lines. The juxtaposition of these charts shows the differences in the frequency of each language, and distinguishes from each other which was placed under the umbrella of “non-English languages”.

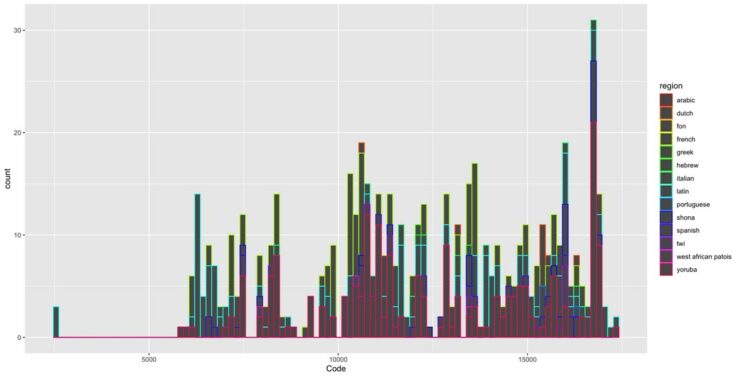

This bar chart is the combination of each singular charts above in one coordinate system. The multiplicity of languages makes it difficult to recognize the pattern of each language, which instead conveys the impression of entanglement among the languages through overlaps. Compared with the clarity in the juxtaposition diagram, this combination chart captures the multilingual feature of the text which breaks the boundaries of and within languages.

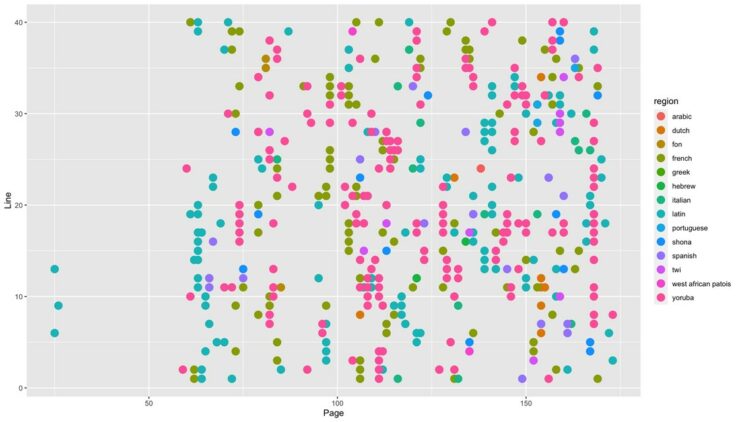

The scatter plot represents the distribution of non-English words in the book with an horizontal axis as the page number and the vertical axis as the line number. In contrast to the bar charts, this diagram does not reflect the appearance of the word through a temporal process. Rather, it focuses on the relational position of each non-English language inside a spatial structure of the book, where the characteristic of entanglement among languages can also be found.

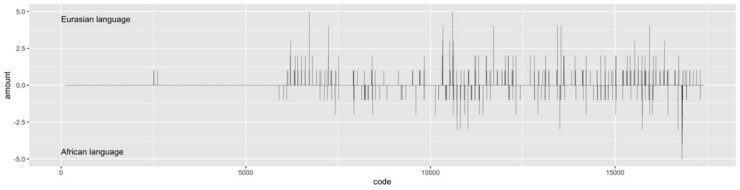

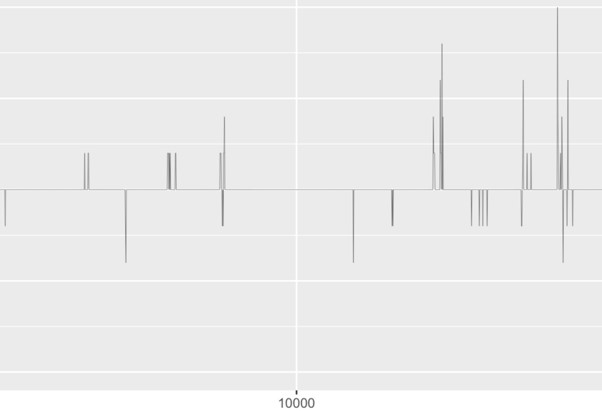

Based on the diagrams above, the line graph and its close-up show my attempt to situate the languages back in the specific historical context of colonialism of Zong massacre. By categorizing the languages into Eurasian language and African language, the line graph here represents the encounter of the two different kinds of languages in the reading process with Eurasian language taking the positive axis and African language the negative axis. The fluctuations reflect the shifts between languages and the flat line refers to English words as well as the blanks. While demonstrating the amount of words and the pace of appearance of the two groups of languages, this line graph shows a contrast between the languages of two group of people, namely, the colonizers and the colonized. By placing African language on the negative axis, it mimics the submergence of African language under the dominance of European languages, while the fierce fluctuations indicates the vigor of African languages and visualize the tension in the circumstances of a slave ship.

Different from the impression of a totality with entangled languages in the former diagrams, the line graph draws attention to the struggle and conflicts between languages in its contrastive form, which refers to the involuntary and brutal aspect of the process of entanglement and creolization. Imitating the electrocardiogram, a record of the patient’s heartbeats, the graph emphasizes the practice of languages as a bodily experience, and arouses the image of death and murder in the process of sailing and reading. The intense and irregular wave of words as heartbeats can be associated with the deterioration of health in the harsh environment, which leads to contemplations of traditional medicine in African cultures through religions and spirituality which is in line with the large amount of names of African deities in Zong!.

Apart from electrocardiogram, the line graph also takes the shape of an audiogram, reflecting the transmission of voices. It indicates the different circumstances of utterance of the languages and the absence of voices, and raises the questions of how the voices linger on in memory and echoes through time and space underneath the consciousness of the languages in Jamaica and the Caribbean countries today.

Last but not least, it is worth considering the process of our picture making, particularly the tool we used. As a programming language operating in the digital space, it seems to be neutral and bears no burden of the history of colonialism. However, the inequity in education and cultural capitals influences the possible accessibility and mastery of this language, which is rooted in the interwoven history of global economics and politics. Both the languages we analyzed and the language we used for analysis show that what resides in each language is always at the same time the past and the present, and the awareness of their inseparable relations makes it possible to envisage a future for all.

Works Cited

Brathwaite, Edward Kamau. “Creolization in Jamaica.” Post-Colonial Studies Reader, edited by Bill Ashcroft, et al., Taylor & Francis Group, 1994, pp. 202-205. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uunl/detail.action?docID=3060300.

Brathwaite, Edward Kamau. “Nation Language.” The Post-Colonial Studies Reader, edited by Bill Ashcroft et al., Routledge, 2006, pp. 309–13. Philip, M. NourbeSe. Zong! Wesleyan University Press, 2011.