Caribbean

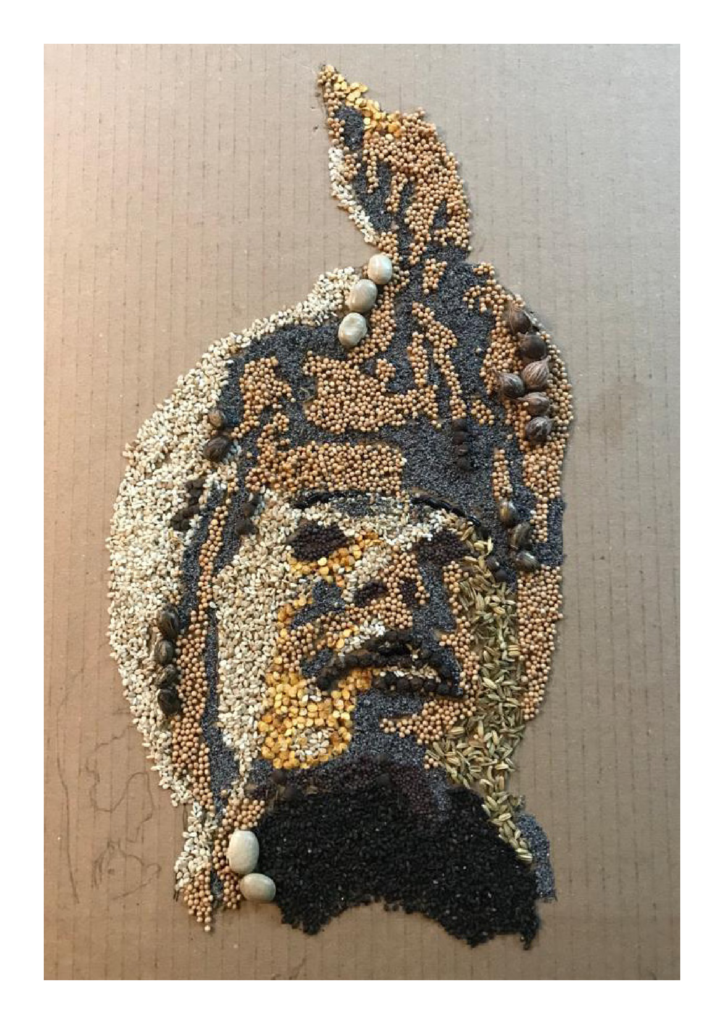

An Ethnobotanical Portrait of a Creole Woman – Luka Hattuma

This portrait of a Creole woman is made of thirteen different seeds on a side of an old cardboard box. Taking an ethnobotanical viewpoint, the aim of this portrait is to visualize the intermingled identity of Creole beingness, both on a cultural level as well as on an ecological level. Since 1492, plants, people and animals have been circulating widely, which caused significant geopolitical changes (Carney “African” 167). During the transatlantic slave trade, the plantations mushroomed in the Caribbean, and as many slaves arrived and were forced into slave labour, various identities became intermingled. In an attempt to get closer to the true meaning of Creoleness, I decided to follow an ethnobotanical path, which has been part and parcel of Indigenous knowledge and passed on for generations before it became a scientific mode of inquiry.

There is a traditional “Maroon narrative” on which this project is based, that is, the practice of women to braid seeds in their hair. Traditional braiding techniques allowed these women to transport the most significant seeds in new environments, using their head and hair as a “celeiro”, which is Portuguese for “barn” (Carney “Arroz Negro” 259). This allowed the women to invisibly transport the seeds, both on land and on sea. When bringing their own seeds and their ethnobotanical knowledge, the slaves were able “to ward of hunger, diversify their diet, reinstate customary food preferences, and to treat illness.” (Carney “Seeds of Memory” 30). Consequently, ethnobotanical values were established anew in a Caribbean context in the little (and limited) fields used or – in exceptional cases – owned by slaves. The slaveholders in their turn, when discovering the potential of these (mostly African- and Caribbean) indigenous plants, used them for their own use, or sometimes started to exploit them overseas (Voeks 277-278). In the maroon cases specifically, the runaway slaves brought their seeds with them when escaping their masters. The slaves, both in and outside plantations, increased and diversified the local flora and fauna with their “experimental stations.” (Voeks 278; Carney “African” 167-171). The intermingling of Indigenous knowledge of the maroons and of the Indigenous communities of the Caribbean became not only a way of surviving, but also, and more importantly, a way of resistance towards their imperialistic masters and intruders respectively (Carney “Seeds of Memory” 29-30). Even today, many descendants still use, or are familiar with, such ethnobotanical practices of the past.

The portrait is inspired by a photograph made by a French photographer Maël Renault, that is called “La Femme Creole” which is part of his photo collection “Caribbean Portrait.” The portrait shows a young Creole woman looking into a distance, while exuding self-confidence and agency. Being Creole involves “the international or transnational aggregate” (Bernabé, et al. 891) of “a nonharmonious mix of linguistic, religious, cultural, culinary, architectural, medical, etc. practices.” (Bernabé et al. 893). The seeds in their turn, originate from many different parts of the world. Similarly to Creoleness, the botanical heritage and the seeds have a rather dynamic and complex form of existence from which the rhizomic roots don’t lead to one single narrative. According to Bernabé et al., Creoleness is rooted in orality, which “contains a whole system of countervalues” that is “devoted to survival.” (895).

As ethnobotanical knowledge was passed on orally among the slaves, maroons and Indigenous people, it is part and parcel of precisely this Creoleness. And the seeds are the existing prove of their mosaic stories.

Works Cited

Bernabé, Jean., et al. “In Praise of Creoleness.” Callaloo, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 886-909.

Carney, Judith. “African Traditional Plant Knowledge in the Circum-Caribbean Region.” Journal of Ethnobiology, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 167-185.

—. “Arroz Negro. As Origens Africanas do Cultivo do Arroz nas Américas.” Bissau: Instituto da Biodiversidade a des Áreas Protegidas, 2018, pp. 250-256.

—. “Chapter 2. Seeds of Memory: Botanical Legacies of the African Diaspora.” African Ethnobotany in the Americas, edited by Robert Voeks and John Rashford. Springer, 2013, pp. 13-33.

—. & Richard Nicholas Rosomoff. In the Shadow of Slavery. Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World. University of California Press, 2009.

Voeks, Robert. “Chapter 12. Traditions in Transition: African Diaspora Ethnobotany in Lowland South America.” Mobility and Migration in Indigenous Amazonia: Contemporary Ethnoecological Perspectives, edited by Miguel N. Alexiades. Berghahn Books, 2009, pp. 275-294.